Imagine walking into a coffee shop and being unable to recognize your own spouse sitting at a corner table. Or having a colleague wave enthusiastically at you while you stare blankly, scrambling to place their identity. This isn’t rudeness or forgetfulness—it’s the daily reality for people with prosopagnosia, commonly known as face blindness. For those living with this neurological condition, the world is populated by strangers, even when it’s filled with loved ones.

The term prosopagnosia comes from the Greek words prosopon (face) and agnosia (ignorance). First identified in the mid-20th century, the condition gained wider recognition through case studies of individuals who, after brain injuries, lost the ability to recognize familiar faces. Today, researchers understand that it can also be congenital, present from birth without any brain trauma. Estimates suggest that up to 2% of the population may experience some form of face blindness, though many go undiagnosed, attributing their struggles to poor memory or social awkwardness.

Living with prosopagnosia is like navigating a world where everyone wears identical masks. Those affected often rely on alternative cues—voices, hairstyles, gait, or distinctive clothing—to identify people. A close friend might be indistinguishable from a stranger until they speak. Some develop intricate mental databases: Sarah has curly red hair and always wears bold jewelry; Mark walks with a slight limp. But these systems are fragile. Change a hairstyle, swap glasses, or encounter someone out of context, and the carefully constructed identification crumbles.

The social ramifications are profound. Casual interactions become minefields. "I’ve ignored bosses at parties, walked past relatives in airports, and once failed to recognize my own mother in a supermarket," shares Emma, a graphic designer with congenital prosopagnosia. The fear of offending others leads many to develop avoidance strategies—generic greetings, vague compliments, or simply pretending to remember. Ironically, this can make them appear aloof or self-absorbed, compounding the isolation.

Romantic relationships require extraordinary adaptation. Partners describe learning to announce themselves verbally upon entering a room ("It’s me, John!"). One man recounts how his wife, after cutting her long hair short, had to reintroduce herself when he returned from a business trip. Children with prosopagnosia may struggle to find their parents at school pickup, while parents might accidentally confuse their twins. These moments, though sometimes humorous in retrospect, underscore a relentless anxiety: Who am I supposed to know right now?

Workplace challenges abound. Networking events are nightmares. A teacher with prosopagnosia might mistake students outside their classroom; a doctor could fail to recognize a frequent patient. Some choose careers with minimal face-to-face interaction, while others disclose their condition preemptively. "I start meetings by saying, ‘I’m terrible with faces, so please remind me how we know each other,’" says Daniel, a journalist. This transparency often disarms potential awkwardness but requires vulnerability many aren’t comfortable sharing.

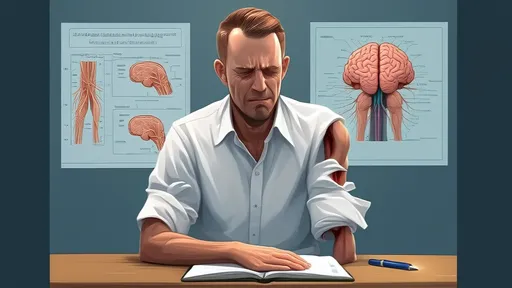

Neurologically, prosopagnosia illuminates the brain’s specialized face-processing machinery. In most people, the fusiform gyrus—a region behind the ears—activates uniquely when viewing faces. Brain scans of those with face blindness show muted activity here. Intriguingly, many retain the ability to perceive facial features (eyes, nose, mouth) but cannot synthesize them into a recognizable whole. It’s like seeing puzzle pieces that refuse to form a picture. Some researchers theorize that the condition exists on a spectrum, with severe cases representing just one extreme.

Diagnosis remains informal—no medical blood test or scan definitively confirms it. Instead, clinicians use face-recognition tests or detailed interviews about life experiences. Treatment focuses on compensatory strategies rather than cures. Mnemonic devices, name tags, or smartphone apps that log acquaintances’ distinguishing traits can help. Emerging technologies like augmented reality glasses that discreetly display names hold promise. Yet accommodations are scarce compared to more visible disabilities. There are no prosopagnosia parking spots or priority seating.

The emotional toll is often underestimated. Many describe a persistent loneliness, even in crowds. "You feel like an outsider in your own life," confides Lara, who wasn’t diagnosed until her 30s. Support groups and online communities provide solace, offering spaces where "Have we met before?" isn’t taboo. Increasing awareness also helps—celebrities like neurologist Oliver Sacks and actor Brad Pitt have spoken about their face blindness, reducing stigma.

Perhaps the greatest irony of prosopagnosia is that it renders the most universal human connection—the face—into a cipher. Yet those who live with it develop extraordinary perceptual workarounds, attuning to nuances others overlook. In a world obsessed with first impressions, they remind us that recognition runs deeper than visuals. As one patient poetically phrased it: "I may not know your face, but I will remember how you make me feel." That, in the end, is the essence of knowing.

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025