The Silent Invasion: How Microplastics Are Reshaping Human Evolution From the Womb

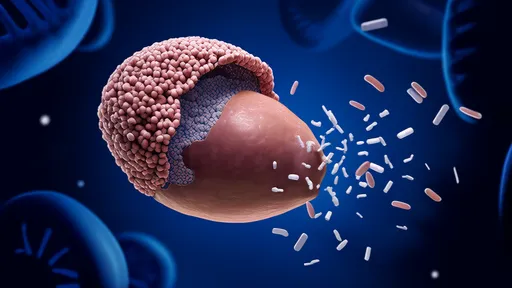

The discovery of microplastics in human placentas has sent shockwaves through the scientific community, revealing an unprecedented environmental intrusion into human biology. These tiny plastic particles, some smaller than a human hair's width, have breached what was once considered nature's most sacred barrier. Researchers examining placental tissue have identified synthetic fragments that shouldn't exist in this vital organ - the temporary interface between generations that has nourished human life for millennia.

This contamination represents more than just pollution; it marks a fundamental shift in the human evolutionary environment. For the first time in our species' history, developing fetuses encounter synthetic materials during their most vulnerable developmental stages. The long-term consequences remain unknown, but the implications could ripple through generations. Scientists speculate these foreign particles might alter fetal development, influence gene expression, or trigger inflammatory responses that could predispose individuals to health issues later in life.

The mechanisms by which microplastics reach the placenta reveal much about our contaminated world. These particles enter our bodies through multiple routes - the food we eat, the water we drink, even the air we breathe. Once inside, their tiny size allows them to hitch rides through the bloodstream, potentially crossing biological barriers that evolved to keep out natural toxins but never faced synthetic intruders. Some studies suggest an average person might ingest a credit card's worth of plastic every week through various exposure pathways.

What makes placental contamination particularly alarming is the organ's critical role in filtering harmful substances while allowing nutrients to pass. The placenta's selective barrier, refined over millions of years of evolution, appears powerless against these artificial invaders. Researchers have found various plastic types in placental tissue, including polyethylene used in plastic bags and bottles, and polypropylene found in food containers. These materials often contain chemical additives that might leach into fetal environments.

The timing of exposure could prove crucial to understanding potential impacts. During embryonic and fetal development, biological systems establish fundamental structures and functions through precisely timed processes. Even minor disruptions during these sensitive periods can have outsized effects. Some researchers draw parallels with historical environmental contaminants like lead or tobacco, where health consequences took decades to fully understand.

Beyond immediate health concerns, microplastic contamination raises profound questions about human evolution moving forward. Evolutionary pressures now include synthetic particles interacting with our biology in ways nature never prepared us for. Some scientists speculate this could lead to selective pressures favoring genetic variations that better tolerate or eliminate plastics, potentially altering human biology over generations. Others warn that the rapid pace of plastic pollution outpaces any possible evolutionary adaptation.

The global scale of contamination leaves no easy solutions. Microplastics permeate every ecosystem, from mountain peaks to ocean depths, making complete avoidance impossible. Even proposed technological solutions like advanced filtration systems or biodegradable alternatives address only part of the problem. The plastics already in our environment will continue breaking down into smaller particles for centuries, maintaining a constant background level of exposure.

This crisis demands reevaluating humanity's relationship with plastic at fundamental levels. The same durability that made plastics revolutionary now makes them persistent pollutants in biological systems. Some researchers argue we've reached a turning point where plastic's convenience no longer justifies its biological costs. Others call for urgent research into how these particles interact with human development and what interventions might mitigate potential harm.

The discovery of microplastics in placentas serves as a stark reminder that human health cannot be separated from environmental health. As the boundaries between our synthetic world and biological systems blur, we face unprecedented questions about what it means to be human in an age of artificial omnipresence. The answers may determine not just individual health outcomes, but the very trajectory of our species' future development.

While research continues, one thing becomes clear: the age of purely natural human evolution has ended. We've introduced a new variable into our biological equation - one whose full consequences future generations may spend centuries unraveling. The plastic genie cannot be put back in the bottle, but understanding its effects might help us navigate this uncharted territory in our evolutionary journey.

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025