The vast expanse of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a swirling vortex of plastic debris twice the size of Texas, has long been a symbol of humanity’s environmental negligence. Yet, in a twist of ecological irony, scientists are now discovering that this floating wasteland is giving rise to something entirely unexpected: a new ecosystem. Dubbed "plastispheres," these microhabitats are teeming with life, from bacteria to barnacles, all thriving on the very material that was meant to be indestructible waste. The emergence of these plastic-bound communities is forcing researchers to rethink the boundaries of life and the unintended consequences of pollution.

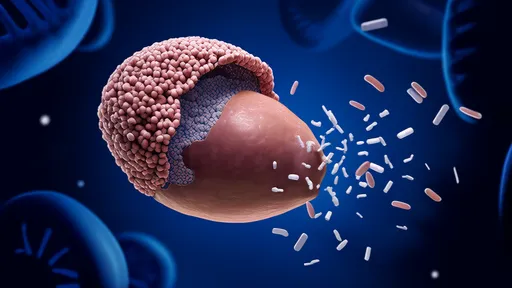

For decades, the garbage patch has been viewed as a barren, lifeless zone, a testament to the destructive power of human consumption. But recent expeditions have revealed a startling truth: the plastic debris is not just inert trash. It has become a substrate for life, a floating reef of sorts, where organisms have adapted to survive in an environment dominated by synthetic polymers. "We’re seeing a colonization event in real time," says Dr. Linsey Haram, a marine ecologist who has studied the plastisphere. "These organisms aren’t just tolerating plastic—they’re using it as a home, a breeding ground, even a food source."

The inhabitants of this new ecosystem are as diverse as they are resilient. Microbes capable of breaking down plastic polymers have been found alongside filter-feeding invertebrates like bryozoans and hydroids. Even larger creatures, such as crabs and fish, are now frequently spotted among the debris, suggesting that the plastisphere is becoming integrated into the broader marine food web. "It’s a paradox," notes Dr. Haram. "The same material that’s killing sea turtles and seabirds is also supporting life. It’s not a good thing, but it’s fascinating."

One of the most surprising discoveries is the presence of "plasticrust," a new type of biological crust formed when microorganisms colonize weathered plastic surfaces. These crusts, which resemble lichen or coral, are not just passive hitchhikers—they’re actively altering the plastic’s chemical composition, potentially accelerating its breakdown. Some scientists speculate that over centuries, these processes could lead to the evolution of entirely new species uniquely adapted to a plastic-dominated world. "We might be witnessing the birth of a post-natural ecology," says Dr. Haram. "These organisms are writing their own rules."

Yet, the plastisphere’s emergence raises troubling questions. While some hail these adaptations as a sign of nature’s resilience, others warn that they could mask the true cost of plastic pollution. If ecosystems begin to rely on plastic as a foundational element, removing it could destabilize entire food chains. Moreover, the long-term effects of plastic-eating microbes are unknown—could they release harmful byproducts or disrupt nutrient cycles? "We’re playing with fire," cautions Dr. Haram. "Just because life finds a way doesn’t mean we should let it come to this."

The ethical implications are equally fraught. If plastic becomes a permanent fixture of marine ecosystems, does that absolve humanity of the need to clean it up? Or does it make the task even more urgent? Some activists argue that the plastisphere is a distraction from the root problem: the unchecked production of single-use plastics. "Celebrating life on garbage is like praising a tumor for being creative," says environmentalist Maria Torres. "The goal should be prevention, not adaptation."

For now, the plastisphere remains a frontier of scientific inquiry, a living laboratory where the boundaries between natural and artificial blur. Researchers are racing to document its species, map its interactions, and predict its future. One thing is certain: the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is no longer just a graveyard for waste. It’s a cradle for life—a stark reminder that in the Anthropocene, even our mistakes can become habitats.

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025