The discovery of marine fossils atop Mount Everest stands as one of geology's most poetic paradoxes—a silent testament to our planet's restless dynamism. These ancient relics, embedded in the world's highest limestone and shale layers, whisper of an era when the summit was submerged beneath primordial seas. For scientists and dreamers alike, they serve as both evidence and allegory: tangible proof of tectonic drama and a metaphor for nature's capacity to rewrite its own history.

When the Roof of the World Was Ocean Floor

To find seashells at 8,848 meters above sea level requires a radical reimagining of Earth's chronology. The fossils in question—primarily crinoids, brachiopods, and other Paleozoic-era organisms—date back approximately 450 million years to the Ordovician period. At that time, the Indian subcontinent was part of Gondwana, drifting near the Antarctic Circle, while the Tethys Ocean covered what would become the Himalayas. The calcium carbonate skeletons of these creatures accumulated on the seafloor over millennia, eventually compacting into the distinctive yellow-band limestone visible today near Everest's summit.

The journey from seabed to sky began when India, propelled by convection currents in Earth's mantle, embarked on its 6,000-kilometer northward migration. Around 50 million years ago, this continental raft collided with Eurasia at about 15 centimeters per year—roughly the speed at which fingernails grow. The resulting collision didn't so much push the land upward as crumple it like a rug forced against a wall, stacking multiple thrust faults that elevated former ocean sediments to staggering altitudes. This ongoing process, called continental subduction, continues to raise the Himalayas by about 1 centimeter annually.

A Geological Detective Story

Early mountaineers dismissed fossil sightings as hallucinations induced by altitude sickness until Swiss geologist Augusto Gansser confirmed their existence during the 1936 Everest expedition. Modern analysis reveals these fossils aren't mere curiosities but critical pages in Earth's autobiography. The specific types of extinct marine life help date the rock layers, while their chemical composition acts as a paleo-thermometer indicating ancient water temperatures. Most remarkably, some fossilized organisms exhibit deformations—visible under electron microscopes—caused by the unimaginable pressures during mountain formation.

Paleoclimatologists have cross-referenced Everest's fossils with similar specimens from the Alps and Appalachian Mountains, reconstructing the Tethys Ocean's expanse. These correlations allowed scientists to trace the ocean's closure like watching a time-lapse of a shrinking pond. The same fossil species appearing across separated mountain ranges became smoking-gun evidence for plate tectonics theory during its controversial mid-20th century emergence.

Time Capsules With Multiple Locks

Unlike typical marine fossils found at lower elevations, Everest's specimens underwent extreme metamorphosis. The combination of tectonic stress and chemical reactions transformed their original structures into metamorphic minerals while preserving their forms—a process akin to a medieval scribe's vellum being pulped and remade as modern paper yet retaining its text. This dual nature makes them invaluable: their shapes tell biological stories while their mineralogy reveals geological processes.

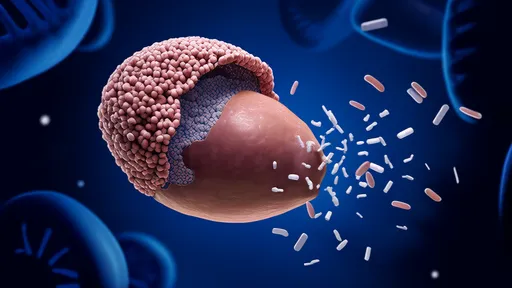

Radiolarian microfossils—plankton with intricate silica skeletons—proved particularly resilient. Their presence in Everest's summit pyramid helped solve a long-standing mystery about the mountain's uppermost layers. Previously thought to be volcanic in origin, chemical analysis showed these rocks were actually deep-sea chert formed from radiolarian remains, confirming that even Everest's peak originated below water.

Beyond Scientific Significance

For Sherpa communities, these fossils have spiritual dimensions. Some consider them saligrams—manifestations of Vishnu, often found as ammonite fossils in Himalayan rivers. Western climbers frequently describe emotional reactions upon encountering fossils during ascents; the juxtaposition of fragile ancient life forms against the brutal high-altitude environment evokes profound reflections on time's scale.

The fossils also serve as unintended conservation ambassadors. As melting glaciers expose more specimens, researchers note increased public interest in protecting Everest's geological heritage from commercial exploitation. During the 2019 climbing season, Nepalese scientists recovered over 100 kilograms of fossil-bearing rock from the South Col before they could be pocketed as souvenirs.

A Changing Perspective

Recent technological advances allow non-invasive study using portable X-ray fluorescence scanners and 3D photogrammetry, preserving these delicate artifacts in situ. Satellite imaging combined with fossil distribution maps has revealed previously unknown fault lines, helping predict future seismic risks for the region.

Perhaps the greatest lesson from Everest's marine fossils is humility. They remind us that continents move, mountains grow and erode, and that human existence occupies but a geological eyeblink. As climate change accelerates glacial retreat, exposing ever more fossils, these ancient messengers from the deep past may hold unexpected insights about Earth's future.

The next time you see Everest's snowy crown in photographs, consider this: every flake of that summit snow settles upon what was once ocean mud, every howling wind at the peak echoes through what were silent seabeds, and every climber's crampon scratches against stones that knew only the weight of water. In this eternal dance between land and sea, the mountain itself becomes a philosopher, teaching us that permanence is an illusion—and that even the mightiest peaks were once humble ocean floors.

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025