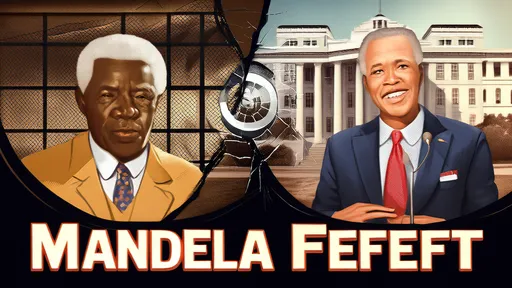

The Mandela Effect has become one of the most intriguing psychological phenomena of our time, sparking debates about memory, reality, and even the possibility of alternate universes. Named after the widespread false memory of Nelson Mandela dying in prison during the 1980s—when in fact he was released and later became South Africa’s president—this effect describes instances where large groups of people remember events or details differently from how they occurred. But what causes these collective memory distortions? Are they merely quirks of the human mind, or is something more mysterious at play?

The Nature of False Memories

Human memory is far from perfect. Cognitive psychologists have long known that memories are not static recordings of events but are instead reconstructed each time we recall them. This reconstruction process is influenced by suggestion, context, and even our own expectations. Studies have shown that people can develop vivid false memories through exposure to misleading information or social reinforcement. In the case of the Mandela Effect, shared cultural references or widespread misinformation could seed similar false memories across large populations.

For example, many people vividly recall the children’s book series being called "The Berenstein Bears", when in reality, it has always been "The Berenstain Bears". This discrepancy could stem from the phonetic similarity between "-stein" and "-stain," combined with the prevalence of names ending in "-stein" in popular culture. Once a few people misremembered it, the incorrect version spread, reinforcing the false memory in others.

Media and the Spread of Misinformation

Another possible explanation lies in the role of media and misinformation. Before the digital age, errors in newspapers, television, or books could propagate widely without easy correction. A misprinted title or a misquoted line from a movie might have been absorbed by thousands of people, creating a shared but inaccurate memory. The line "Luke, I am your father" from Star Wars is often misquoted—the actual line is "No, I am your father." Yet, the incorrect version persists in popular culture, repeated in parodies and references, further cementing the false memory.

In the internet era, misinformation spreads even faster. A single viral post or meme can introduce an incorrect fact to millions, who then integrate it into their own recollections. The speed at which false information circulates today may amplify the Mandela Effect, making it seem more widespread or mysterious than it truly is.

Conspiracy Theories and Alternate Realities

Some proponents of the Mandela Effect take a more speculative approach, suggesting that these discrepancies are evidence of parallel universes or reality shifts. According to this theory, small groups of people may have "shifted" from an alternate timeline where certain events or details were different. While this idea is fascinating, it lacks scientific support. Neuroscientists and psychologists generally attribute the Mandela Effect to the fallibility of human memory rather than glitches in the fabric of reality.

Still, the persistence of these collective false memories raises deeper questions about how we perceive truth. If hundreds or thousands of people can confidently remember something that never happened, how much of our shared reality is truly objective? The Mandela Effect serves as a reminder that memory is malleable and that even widely held beliefs can be mistaken.

Conclusion: A Mirror to Human Cognition

Rather than pointing to a grand conspiracy or interdimensional travel, the Mandela Effect likely reveals the quirks of how our brains store and retrieve information. Memory is not a perfect archive but an interpretive process shaped by social, cultural, and cognitive factors. While it’s tempting to imagine hidden forces altering our past, the truth may be even more unsettling: our own minds are the architects of these false realities.

As we continue to explore this phenomenon, the Mandela Effect challenges us to question not just what we remember, but how we remember—and why so many of us remember the same things incorrectly. Whether through linguistic confusion, media influence, or simple cognitive bias, these collective memory lapses remind us that reality, as we perceive it, is always a step removed from absolute truth.

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025